by Katherine Knight …

In the past three months, I have had the opportunity to reflect on two museum experiences. Memberships of the Australian Museum were family Christmas gifts this year, with the primary intention of introducing two little preschoolers to some of the wonders of science, nature and culture. The museum is Australia’s oldest, founded in 1827 ‘when natural history was at the cutting edge of modern thinking’. From being housed in a shed, formerly the post office, it moved into its first official building opened in 1857. Since then, there have been many additions and expansions on the site now bounded by College and William Streets, Sydney.

Last year, we made two visits to the museum – both to see Tyrannosaurs – Meet the Family, an extraordinary multimedia experience showcasing the newly-revised tyrannosaur family tree. The exhibition was produced by the museum itself and was truly immersive. Dinosaurs rumbled in warning and then appeared loping around Sydney’s Circular Quay. Scary but exciting. Children could run and jump in a special floor space and watch as dinosaurs ran through doorways to check the disturbance. Fossils, casts of skeletons and interactive screens fleshed out the history.

Last year, we made two visits to the museum – both to see Tyrannosaurs – Meet the Family, an extraordinary multimedia experience showcasing the newly-revised tyrannosaur family tree. The exhibition was produced by the museum itself and was truly immersive. Dinosaurs rumbled in warning and then appeared loping around Sydney’s Circular Quay. Scary but exciting. Children could run and jump in a special floor space and watch as dinosaurs ran through doorways to check the disturbance. Fossils, casts of skeletons and interactive screens fleshed out the history.

This year, radical change is evident as the museum is reconfigured under director Kim McKay AO, now in her second year in this role. Work continues on creating a new, easily accessible crystal glass entrance and new displays.

Garrigarrang: Sea Country has already been open for six months in the upgraded Indigenous Australian galleries. In the words of co-curator Amanda Jane Reynolds, the concept behind the development of Garrigarrang: Sea Country is ngara – to listen to Elders in the local Sydney Aboriginal language. ‘Hear what Country is saying and think how our actions will impact all living things. Ngara is the path to knowledge, wisdom and survival.’ The atmosphere is respectful; it invites listening and enquiry. ‘Elders, makers and communities from many Sea Countries around Australia are represented through stories, songs, artwork, films, and cultural and scientific knowledge and technologies.’ At the entrance to the exhibition, a film shows Auntie Julie Freeman telling a story handed down from her Dharawal grandmothers – Narawarn and the coming of the Sea. As she relates the story of Narawarn and his older brother Arrilla, her gentle voice and the expression on her face of complete absorption become compelling. My four-year-old granddaughter sat and listened as we watched Auntie Julie’s eyes fill with tears as Narawarn’s had done and we glimpsed the depth of scientific, cultural and spiritual wisdom, encompassed by the creation story. In fact, the little girl asked me to tell her the story again, seeming to accept it with natural wonderment.

A storyboard in the exhibition says the museum has a special place where Indigenous people can come and record their stories for future generations or ask for cultural information that may have been lost.

With this recent experience still resonating in my head, I visited the American Museum of Natural History in New York in July this year.  The first impression was one of enormity. The main entrance, off Central Park West, at 79th street, opens into the dramatic Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall, which rises two floor levels in height. It was American Independence Day, the height of the summer holiday season and crowds of people surged throughout the building. Signs and floor plans indicated a great range of permanent and changing exhibitions about birds, mammals, human origins and cultures, space and earth sciences.

The first impression was one of enormity. The main entrance, off Central Park West, at 79th street, opens into the dramatic Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall, which rises two floor levels in height. It was American Independence Day, the height of the summer holiday season and crowds of people surged throughout the building. Signs and floor plans indicated a great range of permanent and changing exhibitions about birds, mammals, human origins and cultures, space and earth sciences.

Among the signs were ‘North West Coast Indians’ and ‘Eastern Woodlands Indians’. There wasn’t time to visit them, but I felt uneasy about the titles. Viewing online reveals what I feared – showcases filled with informative material, but none of the sense of connectedness to real people offered by the Australian Museum’s Garragarrang: Sea Country. It felt like the dioramas of traditional Aboriginal life in the Melbourne Museum of my 1940s’ childhood, when it never occurred to me that Aboriginal people and culture were actually still alive in Melbourne.

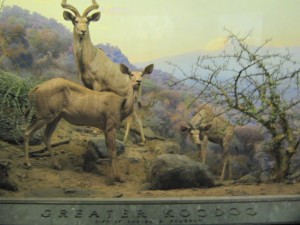

From the Memorial Hall, people flowed into the Akeley Hall of African Mammals. In the darkened centre was a herd of African elephants. On two levels surrounding them were dioramas of animals.

The displays had been funded by private donors, acknowledged under the titles of the displays. The overwhelming sense was of 19th century grandeur. I wondered if the American museum was restricted by the terms of those original endowments. Both the Australian and American museums work constantly to raise funds – private, corporate and government support, memberships and retail sales. Maybe the Australian Museum has been able to negotiate more flexible use of their funds to allow the development of really contemporary and engaging experiences.

The displays had been funded by private donors, acknowledged under the titles of the displays. The overwhelming sense was of 19th century grandeur. I wondered if the American museum was restricted by the terms of those original endowments. Both the Australian and American museums work constantly to raise funds – private, corporate and government support, memberships and retail sales. Maybe the Australian Museum has been able to negotiate more flexible use of their funds to allow the development of really contemporary and engaging experiences.