by Christa Ludlow…

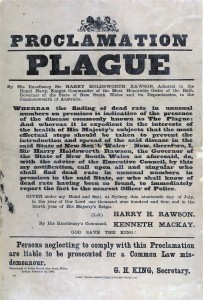

Bubonic plague in Sydney in January 1900 infected 303 people and by August had killed 103. The outbreak coincided neatly with the beginning of the Edwardian era and the rise of the “expert” in public life. I became interested in this part of Sydney’s history while I was researching for my mystery novel, Taken At Night, which is set in Sydney in the early days of the plague. I was particularly intrigued by the character of Dr John Ashburton Thompson, who at the time of the plague outbreak was the President of the Board of Health, a position he had held since 1896. Thompson was a surgeon and physician, educated in London, Cambridge and Brussels, who had come to the colony in 1884. He was a disciple of the new discipline of public health and hygiene. He is credited with first conclusively establishing and documenting the relationship between plague in rats and plague in humans. His reports on the subject became ‘classics’ among the medical profession and he was invited to address medical congresses in the USA and Europe on the subject of the plague.[1]

Bubonic plague in Sydney in January 1900 infected 303 people and by August had killed 103. The outbreak coincided neatly with the beginning of the Edwardian era and the rise of the “expert” in public life. I became interested in this part of Sydney’s history while I was researching for my mystery novel, Taken At Night, which is set in Sydney in the early days of the plague. I was particularly intrigued by the character of Dr John Ashburton Thompson, who at the time of the plague outbreak was the President of the Board of Health, a position he had held since 1896. Thompson was a surgeon and physician, educated in London, Cambridge and Brussels, who had come to the colony in 1884. He was a disciple of the new discipline of public health and hygiene. He is credited with first conclusively establishing and documenting the relationship between plague in rats and plague in humans. His reports on the subject became ‘classics’ among the medical profession and he was invited to address medical congresses in the USA and Europe on the subject of the plague.[1]

Today plague is uncommon but not unknown. Modern doctors would treat it with antibiotics. In 1900 there existed a vaccine of inactivated plague cultures but this was not widely available. Once a person contracted the disease, little could be done but wait and see.

The Chronology of an Epidemic

The first news of the plague apparently caught Thompson by surprise. The Daily Telegraph of 25 December 1899 reported that its journalist had informed him of a fatal plague outbreak in Noumea. Thompson issued instructions to port health authorities that every vessel arriving from a New Caledonian port would be obliged to hoist the yellow flag, and be held in strict quarantine. However, nine passengers had already landed from one steamer and the police had to pursue them through the city and return them to the ship.

Thompson was keen to get supplies of a vaccine, but the nearest supplies were in India. On 28 December he stated that the only remedy was for the Board to make its own.

After repeated representations to import plague bacillus to create the vaccine, the former Premier and Treasurer, Mr Reid, gave his verbal permission. This was renewed by Premier Lyne. Legally, this was a permission which the Premier had no power to give and upon which the Board could not rely. Nevertheless, they started inoculating animals with the plague in secret to increase their knowledge of the disease.[2]

In effect, the Board was unlawfully experimenting with the bacillus something that was fraught with danger. Only the previous year, 1898, I discovered, researchers in Vienna had contracted bubonic plague while conducting similar experiments; several had died. A similar incident in Sydney could have caused public panic and discredited the Board.

The first suspected case of plague was reported on 20 January 1900. He was Arthur Payne, a van driver who worked near the wharves. The second victim, Captain Thomas Dudley, had recently cleared out five dead rats from the watercloset in his Sussex Street premises.

On 14 February the Board of Health received notice that rats were dying around the Huddart Parker and Co and Union Company wharves.[3] It was from a rat found on the Union Wharf that the first positive result of a plague bacillus was obtained. Thompson now had sufficient proof that rats in Sydney had the plague, and it was the same kind as infected humans. Thompson complained on 26 February ‘…the sewerage connections in a vast majority of cases in old houses in the city of Sydney are not at all what they should be…’

Mayor Harris thought differently, complaining that the Board of Health was working the plague ‘for all it is worth as a public sensation’.[4]

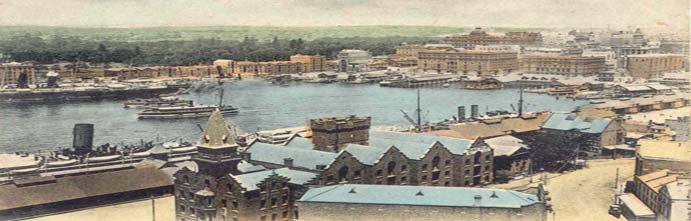

This is the setting for Taken At Night. Ashburton Thompson appears to reveal that the Board has been illegally experimenting on the plague bacillus. The conflict between the medical experts and the political amateurs creates the background for a story set on the wharves, the Quarantine Station and the streets and laneways of The Rocks and Millers Point. The main protagonists are a woman photographer and a police detective. I have tried to capture the atmosphere of the city in 1900, where feminism, eugenics, race theories, socialism and new technologies were all jostling for attention.

This is the setting for Taken At Night. Ashburton Thompson appears to reveal that the Board has been illegally experimenting on the plague bacillus. The conflict between the medical experts and the political amateurs creates the background for a story set on the wharves, the Quarantine Station and the streets and laneways of The Rocks and Millers Point. The main protagonists are a woman photographer and a police detective. I have tried to capture the atmosphere of the city in 1900, where feminism, eugenics, race theories, socialism and new technologies were all jostling for attention.

In May 1900 large areas of Darling Harbour, Walsh Bay, The Rocks and Millers Point were resumed by the Government and put under the control of a new specialised body, the Sydney Harbour Trust. Swathes of streets, buildings and wharves were demolished. What survived took on a nostalgic patina. Artist Lionel Lindsay and photographer Harold Cazneaux, among others, captured images of tumbledown stone cottages, wharfies on their way to work, and children playing in the street. These were the remnants of a Victorian Sydney that had been doomed by the yellow flag of quarantine.

People may also be interested in a new exhibition at the Aus Nat Maritime Museum ‘Rough Medicine’: http://www.anmm.gov.au/whats-on/exhibitions/on-now/rough-medicine

This sounds like a fascinating novel, Christa. Congratulations. I first ‘met’ Dr John Ashburton Thompson 20 years ago writing the history of Manly Hospital. I remember being rather bemused that he undertook a detailed study to prove that plague rats arrived in Manly on the ferry – as everyone in Manly knew already.

Great to see the blog uncovering these connections!

Looking through the Ashurbon Thompson papers at Sydney Uni many years ago I was astounded to see his comment that, on making an incision in a patient with suspected bubonic plague, the cut further infected the patient who subsequently died- but might otherwise have recovered. How many doctors would admit to that now!

Well done Christa.