by Bruce Baskerville, PHA NSW & ACT Chair.

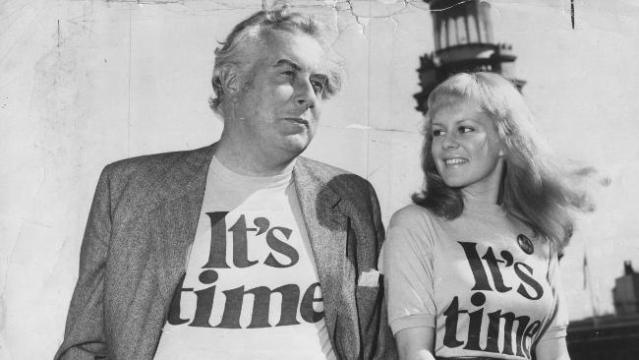

The death of Gough Whitlam on 21 October, Prime Minister between 2 December 1972 and 11 November 1975, has been marked by many obituaries and reminiscences in the media. Fine words have been printed and spoken, far finer than anything I can draw together. So, I would just like to recall some outstanding achievements of the Whitlam governments that, perhaps more than any other, created a social and cultural environment in which ‘heritage’ came to be valued and a Commonwealth responsibility was emphasized and pursued. The Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate, chaired by Justice Robert Hope QC (just notice the fortuitous vocabulary of ‘national estate’, ‘justice’ and ‘hope’) was established in December 1972, and resulted eventually in the Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975, the first Commonwealth legislation that brought together Aboriginal, natural and cultural (or historic, as it was then called) heritage, and in turn open up opportunities for historians to be involved in defining a continental heritage estate, writing and telling its stories, and contributing a historical understanding to its management. That had never happened before. Whitlam’s view that ‘The Australian Government should see itself as the curator and not the liquidator of the national estate’ was as radical then as it is today.

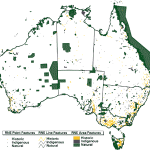

A map of Australia that was unimaginable in 1972:

A map of Australia that was unimaginable in 1972:

Historic, Aboriginal and Natural heritage sites listed in the Register of the National Estate by 2000

My space is too short to wax lyrically, but it is important to recite just a very few of the associated achievements of the Whitlam era, which established the Aboriginal Land Rights Royal Commission in 1973, ratified the World Heritage Convention in 1974 (one of the first countries to do so), commenced building the National Gallery in 1974, revitalized the Australia Council for the Arts, and of course, established the Register of the National Estate in 1975, now sadly reduced to a closed database and the evocative term ‘national estate’ almost forgotten.

It was these actions (and I know I’ve only just touched upon a few) that, I think, first created a demand for historians from outside the academy. I don’t think that was an original intention, but the terms of reference for the Inquiry included how National Trusts and other conservation groups “could be supported by public funds”. The consequent creation of independent professional and public historians who would become an integral part of (in its broadest senses) cultural public policy and management across Australia is, nevertheless, a real outcome and I think the establishment of the first associations for professional historians in Adelaide and Sydney in the mid-1980s needs to be understood in this context.

A more detailed obituary by Guy Betts will be posted on Guy Fawkes Day, also the day of the public memorial service for Mr Whitlam in Sydney.

Bruce’s piece is a fitting tribute. I want to add somehing missed in the metropolitan press about Gough Whitlam’s special legacy in Albury-Wodonga.

His plan for a National Growth Centre was hailed as novel, experimental and imaginative.

It was a pilot scheme which involved three governments entering on an exciting adventure in cooperative federalism.

It was a brave attempt to solve a long-standing problem and a bold venture in selective decentralisation expected to influence the urban settlement pattern in Australia.

The vision was great, but the plans proved difficult to realise as the Whitlam Government was so short-lived.

Whitlam was personally responsible for imagining the rapid and joint development of Albury-Wodonga. He remained an enthusiast and would visit from time to time to hail in endeavours to promote the two cities as one and to upbraid those who set them apart. He was pleased to see that many of the suburbs continued to show their beginnings along the latest New City town planning guidelines. He was proud of the way the district grew as a manufacturing and distribution point. And he would smile quietly at the recognition that even though Albury-Wodonga never reached his population target, it is still ranked in the largest twenty urban cities in Australia.

An early champion of a University of Albury-Wodonga, Whitlam thought it ironic that two universities, one in Albury and the other in Wodonga, endowed him and his colleague Mr Tom Uren separately with honorary degrees for their joint project.