Historians need to become more sophisticated about their audiences. This was the clarion call from the final session of the 2013 Australian Historical Association conference.

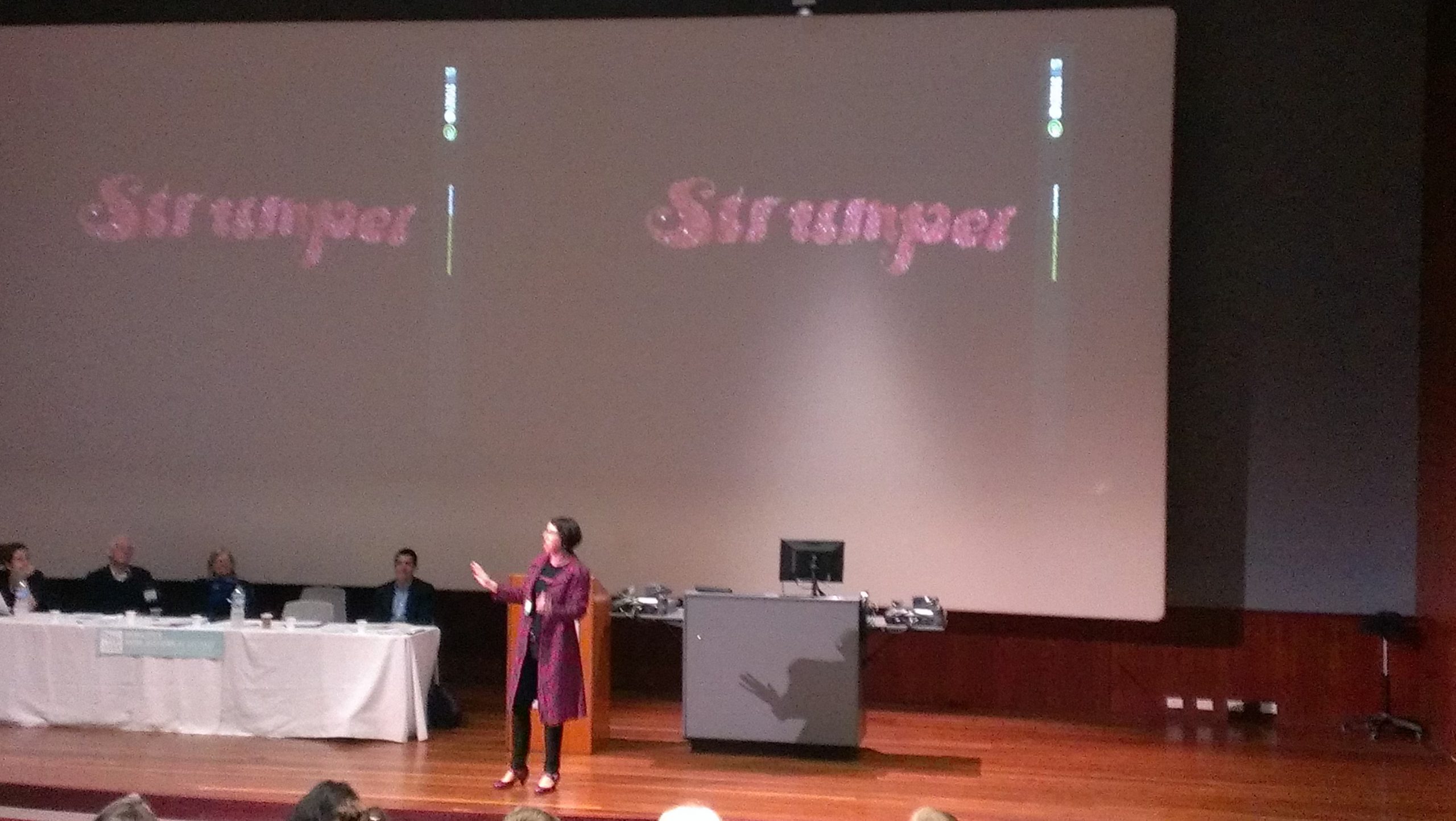

City of Sydney historian, Lisa Murray, declared herself a strumpet for history – prepared to do whatever it takes to promote history. That ‘whatever’ includes better segmentation of audiences and clever marshalling of the new media available to get people engaged. It does not mean dumbing down. In the realm of social media it does, however, open the way for new collaborations between expertise and experience.

All the panellists stressed the importance of keeping the professional historian’s voice heard in discussions about the past. Projecting that voice requires a suite of communication skills: in today’s competitive information market it is no longer possible to rely on the book to convey the message.

Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison underlined the need to acknowledge the viewpoint of one’s audience – without compromising the rigour of the profession. He contended this should be easier for historians than for other scholars, given the former’s devotion to the language of the people and to telling stories, even jokes. Yes, levity is one of the historian’s tools. Indeed, Davison read out an accolade of which he is particularly proud: a local councillor recently praised his book, Car Wars, as ‘amusing and wise’.

Davison reminded us that fellow professionals are one of our audiences. Historians need to communicate with planners and politicians, architects and diplomats. They also need to think carefully about how their work will penetrate the world of Google. A good title and abstract for a scholarly article, along with the right keywords, can send ideas on unexpected travels, beyond the intended reader to many more. So, sometimes it is possible to reach more than one audience with one piece of writing, though all panellists cautioned against assuming that a single product can serve the multiplicity of history’s audiences.

The professional historian, either within the academy or beyond, faces new competitors. Film maker, Sandra Pires, showed us how ordinary people, aided by a digital recorder, are now creating their own histories. Pires acts as an intermediary, tying local stories to those of the professional historian to produce documentaries about big issues that still resonate at the community level.

For many,the personal angle will lead them to history. Nevertheless, the uncertainty that history can cast on the past is not always welcome. Michael Ondaatje, in his elegant speech about the use and abuse of history, warned that the historian’s endless search for new perspectives and their embrace of complexity can be anathema to the broader public. He illustrated his point with references to the Tea Party’s success in invoking history while, in the same breath, dismissing historians whose analyses undermined more comfortable interpretations of the past. Ondaatje appealed to scholars to make contributions beyond the academy. This, he acknowledged, called for more than the individual’s efforts to present history in readable prose: the university system must also better reward those striving for breadth and accessibility rather than just for high journal rankings.

Francesca Beddie, PHA NSW blog editor

Very many thanks for this summary, Francesca – very interesting indeed. It is certainly relevant to my own experience of promoting my book Passion Purpose Meaning – Arts Activism in Western Sydney. I am learning to make very different preparation for each audience I address (mostly non-academic), to use humour and local references and to continue to promote current and future developments through social networking. I hope, of course, that I am disturbing general and media stereotypes about western Sydney, but my interpretations won’t go unchallenged.

Thanks again, Francesca

Thanks Francesca, well worth a blog post that session, definitely one of the most exciting things at the conference. Lisa Murray did a great job of showing what public historians can do to engage people in history.

Great post! There was so much to reflect on from this session. Sandra Pires’ session reminded me of the power of film, a medium which I have not yet explored. It was good to hear that historians are being innovative in telling stories about the past and encouraging informed public debate.

Michael Ondaatje’s suggestion that Steven Spielberg is the most influential or well-known American Historian right now (apologies to Michael, I can’t remember his precise wording) spoke volumes to me. Events which provoke public interest in history, whether they be films such as Lincoln, TV shows, online resources (eg in the many examples provided by Lisa Murray), heritage places, historical fiction books or commemorative events such as Anzac Day and Australia Day, provide powerful opportunities for historians to engage with a broader audience (which come with their own thrills and risks, as Graeme Davison and others have discussed). Many of those who would rather watch a Spielberg film than read an academic book might also be open to broadening their understanding of history. And anyway, most history is already taking place outside of the academic sector. Input by historians with a greater insight into the complexities and intriguing elements of that past can only enhance the public debate.

As a historian working in government, I was also really excited by some of the online initiatives Lisa Murray discussed, and by their potential to reach such large and diverse audiences. Great to see the City of Sydney leading the way in digital history.